The Unification of Italy was a political and social movement in the nineteenth century that resulted in the Unification of the many republics of the Italian Peninsula into a single entity known as the Kingdom of Italy. The Unification of Italy began in the 1840s and was completed in 1871, the same year as Germany’s Unification. This article will provide information on the Unification of Italy and explain the process fully.

Unification of Italy: Introduction

The Congress of Vienna began the process in 1815, and it was finished in 1871 when Rome was designated as the Kingdom of Italy’s capital.

The Unification of Italy took place in two stages. First, it attempted to establish independence from Austria at first. Second, it had to bring all of Italy’s autonomous states together into a unified body. Mazzini and Garibaldi were the most notable revolutionaries during this period.

Italy was nothing more than a geographic statement for many centuries. It was a patchwork of minor states that were envious of one other. Since the Roman Empire, the Italian Peninsula has never been properly united under one rule. Several attempts to unite the Italian Peninsula under a single administration had failed. One of the most significant roadblocks to Italian Unification was the division of Italy among foreign dynasties.

Austria had captured the northern section of Italy. The Hapsburg family of Austrian princes ruled the duchies of Parma, Modena, and Tuscany. The Bourbon dynasty ruled over the Kingdom of Sicily and Naples in the south. Metternich used the term “Italy” as a geographical word because of the country’s fragmentation into numerous separate divisions.

The Pope had temporal jurisdiction over Central Italy. Aside from the Peninsula’s political divide, the Italians had not yet established a genuine sense of national consciousness. As a result, different areas and towns in Italy have evolved their own traditions, resulting in local resentments that stifled national progress. ‘In Italy, the provinces were against the provinces, towns against towns, families against families, and men against men,’ stated historian and statesman Metternich.

During the 1820s

During the 1820s, the Carbonari secret society attempted to organize revolts in Palermo and Naples, but they were largely unsuccessful, owing to the Carbonari’s lack of peasant support. Then there was Giuseppe Mazzini, a patriotic writer who founded the Young Italy national-revolutionary organization (1831). Mazzini advocated for a unified republic. His ideas immediately diffused throughout broad swaths of the Italian people. Revolutionary cells sprang up all over the Italian Peninsula in Young Italy.

In 1846, a new Pope, Pius IX, was elected, promising improvements in the Papal States. Other Italian princes implemented liberal measures to weaken revolutionary forces. Instead, in 1848, these changes sparked revolutions in Sicily, Naples, Rome, Florence, Milan, Venice, and Turin.

The secret organizations, the greatest of which was the Carbonari, or Charcoal Burners, were a major source of agitation. The Carbonari were constantly engaged in stirring up opposition and revolution against foreign control, using the watchwords “freedom and independence.” The enthusiastic leadership of idealists and intellectuals was another crucial aspect of the resurrection’s success. Cavour, Mazzini, and Garibaldi are the three persons most responsible for the restoration of Italian unity.

Let us now describe the process of Italy’s Unification, the Unification of Germany and Italy, and the aftermath and other aspects. For further information on other important topics, go to the UPSC study materials website here.

Explain the Unification of Italy with explanations

In this article, we will describe the roles of three influential leaders in the Unification of Italy.

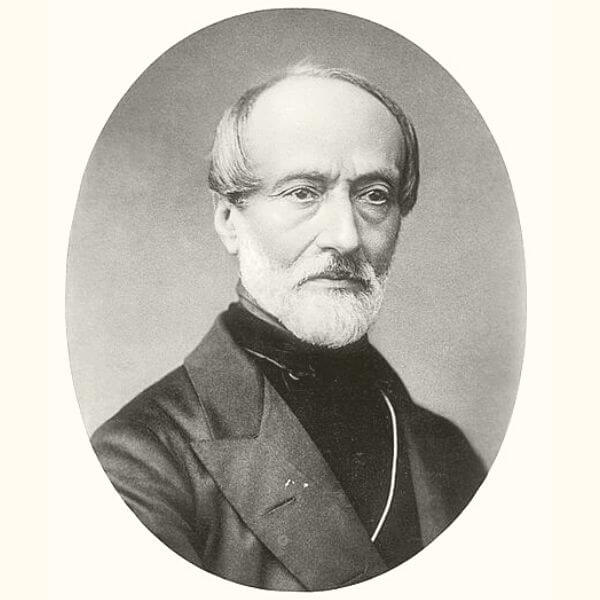

Mazzini (1805- 1872)

- Mazzini was born in Genoa, studied law as a young man, and read the works of democratic thinkers widely. His extreme views drew the suspicion of the authorities, and he was jailed in 1830. Mazzini had already decided on the first step while incarcerated.

- He opted to leave the cause of Italy to young minds and hands after losing faith in Carbonarism, whose leaders were mostly elderly men. He founded the Young Italy society among the Italian exiles in Marseilles in 1832.

- Friends founded the first lodge in Genoa, and it quickly expanded throughout northern and central Italy, largely drawing students, young professionals, and mercantile youngsters.

- The organization’s banner read “Unity and Independence” on one side and “Liberty, Equality, Humanity” on the other. Within two years, the membership had expanded to more than 50,000 people.

- In addition to forming and directing Young Italy, Mazzini produced numerous ardent articles and pamphlets that were smuggled into Italy.

- The Patriots were united in their belief that the only way to achieve unity was to expel the Austrians in whatever shape it took.

- While nationalism shattered empires, it also gave birth to new nations. Italy was one of the countries that arose from the ruins of empires. Between 1815 and 1848, a growing number of Italians felt dissatisfied with living under foreign control.

Cavour (1810-1861)

- Italian nationalists looked to the kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, Italy’s largest and most powerful state, for leadership. In 1848, the monarchy established a liberal constitution. As a result, union under Piedmont-Sardinia sounded like a decent idea to the liberal Italian middle classes.

- By birth, Count Camillo di Cavour was a Piedmontese. In 1847, he took a decisive political step when he co-founded the II Risorgimento, a publication dedicated to the establishment of a Piedmontese constitution. Charles Albert signed the Constitution in February 1848, and Cavour was elected to the parliament under its provisions in June.

- In the year 1852, he was elected Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Cavour put himself wholeheartedly into the task of restoring Piedmont and bringing Italy together. He reorganized the army, erected new fortifications, and expanded military resources as a result. He also focused on the growth of industry and commerce, constructing multiple railways, and negotiating commercial treaties with France, England, Holland, Belgium, and Switzerland.

Cavour Leads the Unification of Italy

- Piedmont also established a strong claim to equality with other states by deploying an army to Crimea. Cavour spoke at the Congress of Paris in 1856, denouncing Austria’s dominance and misrule in the Peninsula. On June 24, 1859, the combined forces of France and Piedmont defeated the Austrians at Magenta and again at Solferino.

- Austria appeared to be on the verge of being fully evicted from Italy. However, Napoleon III abruptly came to a halt and signed the Armistice of Villafranca (July 8) with Emperor Francis Joseph without consulting his ally. Lombardy was added to Piedmont under the terms of the treaty signed in Zurich on November 10, 1859, although Venetia remained under Austrian authority.

- Cavour resigned his premiership in a fit of wrath, but he returned to the fight after a brief respite. Tuscany, Modena, Parma, and Romagna rose against their rulers, declaring unanimity for union with Piedmont, sparked by the zeal of Piedmontese leadership.

- By surrendering Savoy and Nice, Cavour was able to obtain Napoleon III’s approval. Victor Emanuel then acknowledged the annexation of the four Italian states, and on April 2, 1860, an enlarged parliament assembled in Turin, comprising roughly half of the Peninsula’s population.

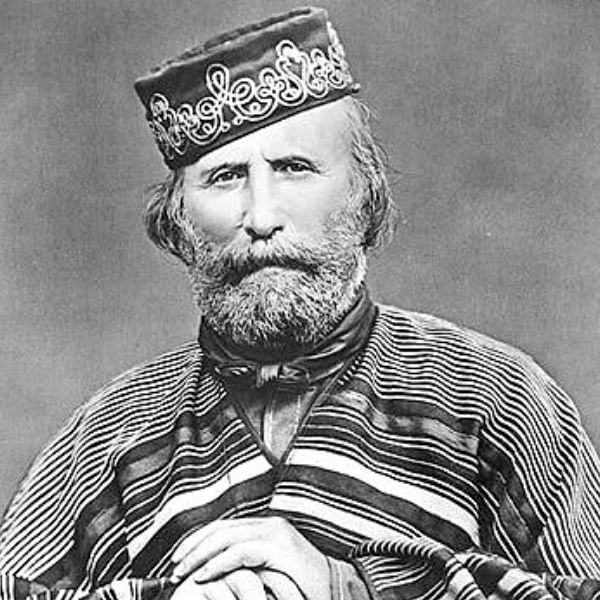

Garibaldi, Giuseppe (1807-1882)

- Garibaldi took the next process towards the Unification of Italy. He joined the Young Italy society as a young man and took part in an attempted insurgency in Genoa in 1833.

- He was sentenced to death but managed to flee the country and travel to South America in 1834. There he learned the art of guerrilla warfare, which he would use to great effect in the conquests of Sicily and Naples.

- Garibaldi and his followers always wore bright red shirts in battle. This is how they got the title “Red Shirts.”

- He overcame his opponents so fast that he was lord of the island in a matter of weeks, after which he crossed to the mainland and marched on Naples nearly unchallenged. When Francis II saw him approaching, he fled, and Garibaldi entered the capital to the delight of the people.

Victor Emmanuel II

- Victor Emmanuel II rode into Naples early in November with Garibaldi at his side to make the annexation official after a plebiscite declared the annexation by a virtually unanimous vote. Garibaldi now considered his work completed. He withdrew to his island, refusing all honors and awards.

- In the meantime, Piedmontese troops had conquered the remainder of the Papal States, with the exception of Rome and a tiny territory around it. The first national parliament representing the north and south met in Turin on February 18, 1861. Victor Emmanuel II was formally dubbed “by the grace of God and the will of the country king of Italy” on March 17, 1861.

- The more arduous stage of the unification process had come to a close. Only Venetia and Rome remained beyond the new kingdom’s borders.

- When Bismarck was preparing to conquer Austria in 1866, he formed an alliance with Italy, promising them Venetia as a reward for fighting on Prussia’s side. The Austrians defeated the Italians on land and at sea. Still, the Prussian victory at Koniggratz on July 3, 1866, was so decisive that Prussia won the war, and Venetia was given to the new kingdom of Italy. The necessities of the Franco-Prussian war in 1870 enabled the acquisition of Rome four years later.

- Victor Emmanuel was welcomed into the Eternal City by the people in July of 1871. Cavour’s and the Italian patriots’ dream, which had elicited laughter in European diplomatic circles a quarter-century before, was realized.

Describe the process of Unification of Italy

- 1849- The Austrian army defeated Venice this year, causing a tremendous upheaval in Venetia by crushing many people.

- 1858- Cavour and Napoleon III decided to wage war on Austria by annexing Venetia, Lombardy, Modena, and Parma to Italy in 1858.

- 1859- Cavour’s return to Venetia and Napoleon III’s withdrawal from the war with Austria were significant events in 1859. In this year, Sardinia conquered Modena, Tuscany, and Parma, as well as Lombardy.

Napoleon III

- 1860- In 1860, Parma, Modena, Tuscany, and the Papal State of Romagna became part of Sardinia-Piedmont. Nice and Savoy were given to Napoleon III.

- Garibaldi landed at Marsala, won Sicily at the Battle of Calatafimi, and crossed the straits to Naples with the stated goal of crowning Victor Emmanuel at the Vatican.

- Cavour intervened to put a stop to Garibaldi’s rash idea, which would have enraged both Austria and France. To halt Garibaldi’s advance on Rome, he dispatched the Sardinian King and army into the Papal States, where the Papal army was destroyed at Castel Fidardo. Garibaldi was postponed a fortnight on the Damage by the Neapolitan army, which was fortunate for Cavour and Italy. After defeating this army, he met Victor Emmanuel at Teano and graciously gave over Southern Italy. The Kingdom of Italy was established in 1861, following the V. Venetia-Austro-Prussian War.

- 1861- “Camillo Di Cavour” died this year after learning that Italy had no control over the Papal States. In Venetia, the official kingdom of Italy was established.

- 1867: Garibaldi wants the Papal States and Rome, despite his attempt failing and the revolt in Rome is put down.

- 1870- The Italian army advanced slowly towards Rome, capturing the city and establishing a stronghold in the town.

- 1871- The unity of Italy(Unification) is accomplished with the relocation of the Italian capital to Rome.

Germany & Italy Unification

The principles of nationalism and enlightenment motivated and affected the people of Europe in the 1800s. Many regions were encouraged by these ideals to rebel against the Europeans and sought independence. Italy and Germany were similarly forced to unite by the principles of nationalism and enlightenment. Neither Italy nor Germany existed in the mid-nineteenth century since they were divided into smaller territories that frequently struggled for autonomy, despite their cultural similarities. These cultural, historical, linguistic, and religious commonalities prompted impulses of nationalism in both Italy and Germany.

Germany was split into 30 states, all of which were allies of the German Confederation. The Austrian Empire ruled this Confederation, but it was the state of Prussia that spearheaded Germany’s union. When Otto von Bismarck was elected Prime Minister of Prussia in 1862, he declared that the only way to achieve his goals of Unification was via blood and war. Over the course of seven years, he fought and won battles with Denmark, Austria, and France. This resulted in Germany’s union, and William I, King of Prussia, was declared Emperor of a unified Germany in 1871. Germany’s and Italy’s unification are classic examples of nation-states.

The Unification of Italy and Germany brought in many new powerful figures, including Giuseppe Garibaldi, Giuseppe Mazzini, and Cavour, whose contributions are engraved in world history. We have described the Unification of Italy and, in short, Germany here.

Unification of Italy: The Aftermath

The unity and administration were done solely for the benefit of Piedmont. The new Kingdom of Italy was formed by renaming the ancient Kingdom of Sardinia and annexing all of the new provinces. Victor Emmanuel II, who inherited his father’s title, was the first king. Piedmont’s old constitution was replaced with the new one. The document was liberal in nature and received positive feedback from liberals.

Pro-clerical areas like Venice, Rome, Naples, and Sicily despised its anti-clerical legislation. Cavour pledged regional, municipal, and local administrations, but in 1861, he broke all of his commitments. Civil wars erupted in Sicily and the Naples region in the first decade of the monarchy, but they were all put down. Many local Italians were nonetheless unhappy with the arrangement, and there was constant turmoil throughout the kingdom, often known as Italian irredentism.

In 1915, Italy joined the 1st World War in order to achieve complete national Unification. It first remained neutral, but when the Treaty of London was signed in 1915, it agreed to join the war against the central powers. Because Italy did not receive the additional territories promised by the Treaty of London, the result was dubbed a “mutilated victory.” Benito Mussolini coined the phrase “mutilated victory,” which aided the establishment of Italian Fascism and became the propaganda of Fascist Italy. The irredentism movement in Italian politics collapsed after World War II.

Conclusion- Unification of Italy

In conclusion, this article will assist you in providing all information relevant to Italy’s Unification. We’ve also talked about Italy’s unification process, Three strong leaders were described, and the Unification of Germany was explained in simple terms. This is a key topic for your UPSC history test. As a result, read carefully and make notes on important points. Also, keep an eye on the UPSC’s official website for the most up-to-date exam information.

FAQ- Unification of Italy

The unification of Germany and Italy shifted Europe’s power balance. In central Europe, a united Germany (rather than Austria) was the most powerful state. The Hapsburg realms were made up of provinces with a wide range of linguistic, cultural, and historical variety.

The Unification of Italy was a political and social movement in the nineteenth century that resulted in the unification of the many republics of the Italian Peninsula into a single entity known as the Kingdom of Italy. The unification began in the 1840s and was completed in 1871, the same year as Germany’s unification.

In 1871, the unification process of Italy ended.

The unification process was accelerated by the Revolutions of 1848, which culminated in the Capture of Rome and its designation as the Kingdom of Italy’s capital in 1871. It was sparked by rebellions in the 1820s and 1830s against the outcome of the Congress of Vienna.

Editor’s Note | Unification of Italy

In summary, this article will assist you with the essential UPSC topic of Italian Unification. We’ve talked about Italy’s Unification and given a described explanation of the process. We have described the roles of three significant leaders in the Unification of Italy. Keep yourself motivated when studying for UPSC or other competitive exams because motivation focuses on the reasons for doing something, as well as the level of desire to do it. If you plan correctly, you will be able to achieve your goals. We wish you the best in your exams.