Ordinance-Making Power in India: Constitutional Limits and Judicial Safeguards

Ordinance-making power allows the executive to legislate temporarily when legislatures are not in session, rooted in Articles 123 and 213 of the Indian Constitution. This mechanism addresses urgent needs but faces strict constitutional limits and judicial scrutiny to prevent misuse. Designed as an emergency tool, it balances efficiency with democratic accountability, making it a frequent topic in GS-II Polity for UPSC exams.

Constitutional Provisions

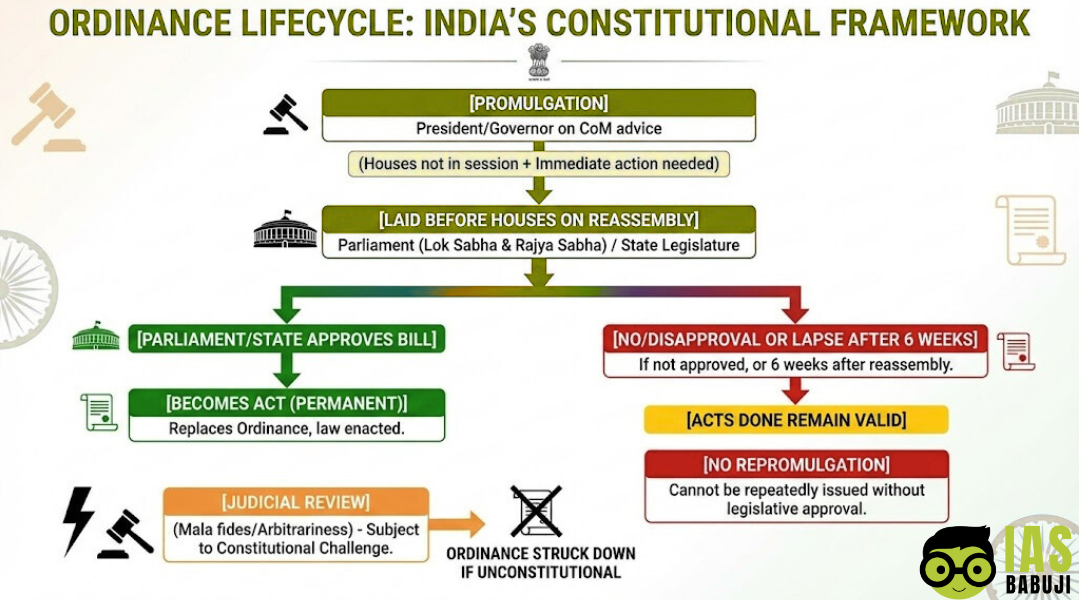

Article 123 empowers the President to promulgate ordinances when both Houses of Parliament are not in session, but only if satisfied that circumstances demand immediate action. These ordinances have the same force as parliamentary Acts, yet must be laid before both Houses upon reassembly and approved within six weeks, or they lapse—yielding a maximum lifespan of six months and six weeks.

Article 213 mirrors this for Governors regarding state legislatures, with ordinances subject to identical procedural safeguards. Neither can amend the Constitution, abridge fundamental rights, or exceed legislative competence; they remain co-extensive with parliamentary powers. Presidents and Governors act solely on Cabinet advice, ensuring this is not a discretionary power.

Ordinances can be retrospective, modify existing laws, or repeal prior ordinances, but repromulgation after lapse is prohibited as it circumvents legislative intent. Acts performed under a lapsed ordinance retain validity, providing continuity despite expiry.

Key Limitations and Conditions

Promulgation requires Houses not in session; ordinances issued otherwise are void, distinguishing this from parallel legislative authority. The executive’s “satisfaction” on urgency is conditional, not absolute, and subject to the same constitutional restrictions as Acts.

Upon reassembly, Parliament or state legislatures have three options: approve via bill (becoming permanent law), disapprove (immediate cessation), or inaction (lapse after six weeks from the later reassembly date). Governors face an extra check: prior Presidential instructions for ordinances needing central sanction, reserved bills, or invalid without assent.

These limits prevent “ordinance raj,” where executives bypass debate. Vague urgency criteria have led to misuse, like re-promulgating without legislative effort, violating separation of powers.

Judicial Safeguards and Landmark Cases

The judiciary has evolved robust review standards, transforming ordinance power from non-justiciable to conditional. In R.C. Cooper v. Union of India (1970), the Supreme Court held the President’s satisfaction challengeable in court, opening doors to judicial scrutiny on grounds like mala fides.

D.C. Wadhwa v. State of Bihar (1987) condemned Bihar’s repromulgation of 259 ordinances over 14 years as a “fraud on the Constitution,” ruling it exceptional only—not a legislative substitute. The Court emphasized ordinances for genuine emergencies, not routine governance.

Krishna Kumar Singh v. State of Bihar (2017) reinforced this, declaring repromulgation unconstitutional and subjecting executive satisfaction to review for arbitrariness, irrelevance, or colorable exercise. It clarified lapsed ordinances’ effects but barred revival without fresh justification. These rulings ensure accountability, aligning executive action with constitutional morality.

Historical Misuse and Contemporary Relevance

India has seen over 700 central ordinances since 1952, peaking under Indira Gandhi (1967-77: 77 issued). Bihar’s excesses highlighted state-level abuse, prompting judicial intervention. Recent examples include the 2014 Securities Laws Ordinance (re-promulgated thrice) and 2010 Indian Medical Council Ordinance (four times), raising circumvention concerns.

Amid farm laws (2020) and COVID responses, ordinances linked current affairs to polity, ideal for 10/15-mark UPSC questions on executive overreach. Evergreen due to debates on separation of powers, it tests analytical skills on judicial evolution.

Utilities and Criticisms

Ordinances enable swift responses to crises, like emergencies or opposition blocks, ensuring unobstructed governance. They fill legislative gaps during recesses, vital in India’s federal setup.

Critics argue they erode democracy by sidestepping debate, fostering “ordinance raj.” Frequent use undermines legislatures, with vague “immediate action” enabling overreach—evident in successive reissues without bills. Reforms suggested include stricter urgency definitions and limits on numbers.

Ordinance Lifecycle

This highlights checks: temporary nature, approval mandate, and oversight.

Comparison: President vs. Governor

| Aspect | President (Art. 123) | Governor (Art. 213) |

|---|---|---|

| Session Requirement | Both Houses not in session | Assembly/Houses not in session |

| Urgency Basis | Satisfied on immediate need | Same |

| Scope | Co-extensive with Parliament | Co-extensive with Legislature |

| Presidential Check | None | Required in 3 cases (sanction/reservation/assent) |

| Laying & Lapse | 6 weeks from reassembly | Same |

| Advice | Union CoM | State CoM |

Similarities dominate, but the Governor’s central oversight strengthens federal balance.

Way Forward for UPSC Aspirants

Link to GS-II themes: separation of powers, federalism, judicial activism. Practice questions like: “Ordinance power as last resort? Discuss judicial stance” (15 marks). Memorize cases (Wadhwa, Krishna Kumar) and stats (e.g., Bihar’s 14-year abuse).

Current linkages: Analyze recent ordinances (e.g., 2025 updates via PRS) for Mains answers. FAQs aid Prelims:

- Max validity? 6 months + 6 weeks.

- Judicially reviewable? Yes, post-1970.

- Repromulgation? Unconstitutional.

This power, when restrained, upholds constitutional ethos—key for civil services success

FAQs on Ordinance-Making Power in India

What is the constitutional basis for ordinance-making power in India?

Article 123 empowers the President for Parliament, while Article 213 grants similar powers to Governors for state legislatures, allowing ordinances when Houses are not in session and immediate action is required.

What are the key limitations on ordinance promulgation?

Ordinances must be laid before Houses upon reassembly, approved within six weeks via bill, or they lapse; they cannot amend the Constitution or exceed legislative competence, and repromulgation is unconstitutional.

How has the judiciary safeguarded against ordinance misuse?

In D.C. Wadhwa v. State of Bihar (1987), the Supreme Court ruled repromulgation as a fraud on the Constitution; Krishna Kumar Singh (2017) made executive satisfaction reviewable for mala fides or arbitrariness.

What is the maximum validity period of an ordinance?

Six months from promulgation plus six weeks from House reassembly, after which it lapses if not converted into an Act.

Can ordinances have a retrospective effect?

Yes, they can apply retrospectively, modify existing laws, or repeal prior ordinances, but only within constitutional bounds.

Why is ordinance power relevant for UPSC GS-II?

It links to separation of powers, federalism, and judicial activism, frequently appearing in 10/15-mark questions amid current debates like farm laws.